POCKET DEVOTIONAL

2018

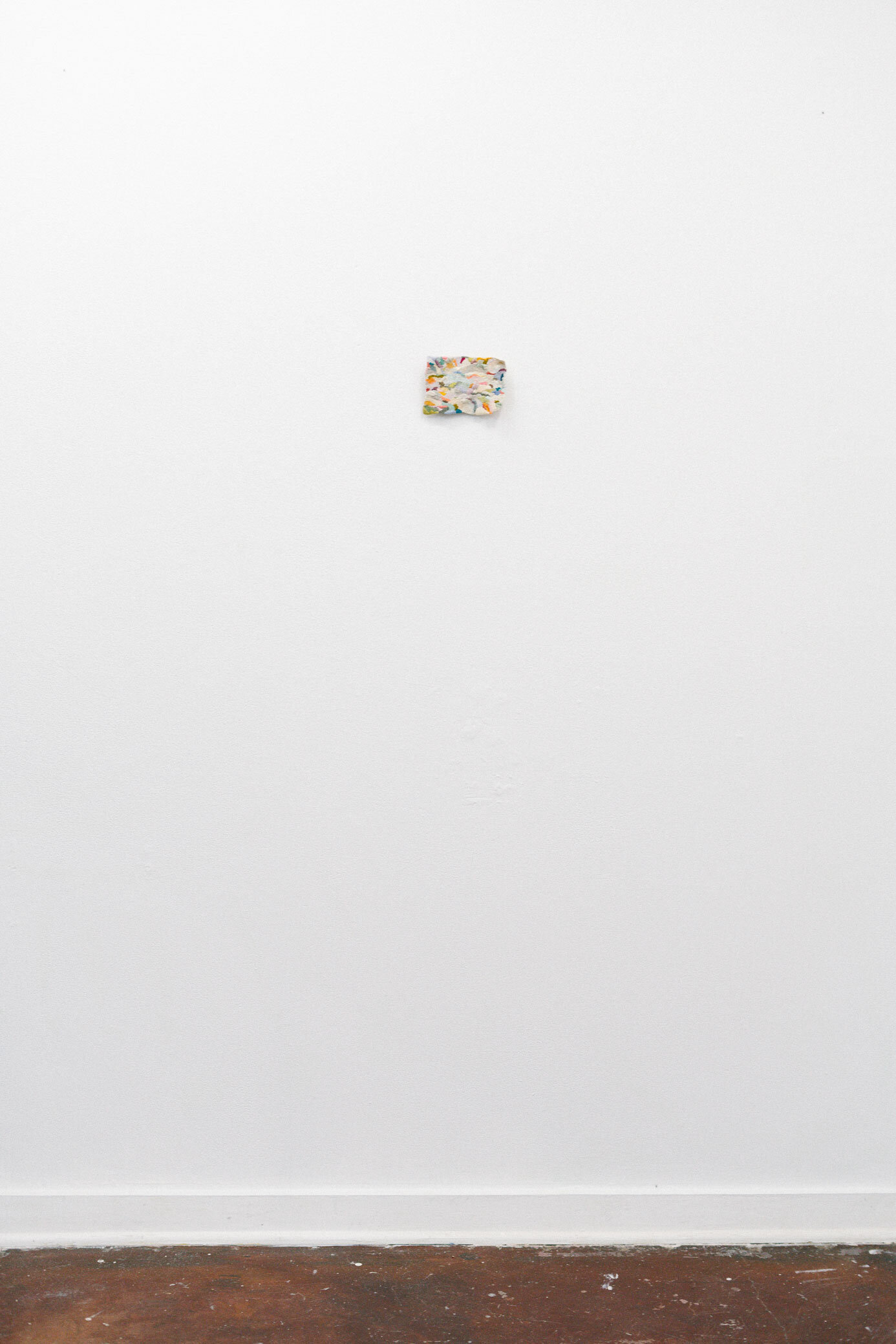

Pocket devotional, 2018, embroidery thread, linen, 10.5 x 15 cm (irreg). Photograph: William Normyle.

Pocket devotional is a palm-sized embroidery, its dense surface warped by stitching. Its title traditionally refers to a miniature book of prayers, hymns, or other religious texts. This intimate work functions as a portable space for meditation or vigil through stitch, in which attention is focused on a hand-sized surface over many dozens of hours. Whilst this ‘devotion’ was conceived as occurring during the making process, the intricacy of the finished piece also provides a surface for contemplation.

HOLD IT IN YOUR HANDS (THE PORTABLE WORLD)

PART 1

Excerpted from the written component of my thesis for Master of Fine Art (Visual Art), 2019. Read Part 2 here.

Pocket devotional, 2019, is a single embroidery the size of a postcard: approximately 15 cm (w) x 10.5 cm (h). Stitched on a piece of lightweight linen without the aid of a stretcher or hoop, the surface is dense and rippled where stitches have pulled the fabric into an almost sculptural shape. Irregular segments of many colours are evoked in seed-stitch and satin-stitch, the forms flowing and organic.

This artwork was made during a period of several months in which I travelled back and forth between Perth and Melbourne, while my father waited for a lung transplant, and as he recovered. I took my work on the plane, back and forth, back and forth: home for a few weeks, then away again, and repeat. I hardly unpacked my suitcase.

In the 18th century, female diarists (for whom needlework was a daily necessity as well as a leisure activity) describe a range of positive emotional responses to their work: it ‘calms the spirits by fixing the attention’, wrote Anna Larpent in 1797, citing embroidery’s ‘monotony & mechanism like the returning sound of water or any other sensation that marks time’. [1] Like Larpent, I craved ‘regular progressive work’ to calm my spirits and fix my attention during this time of emotional and geographic unsettling. I had begun embroidering a dense area on a large banner, but it was impractical to transport or to work on in temporary living spaces. I also felt that I no longer wanted to make a banner: banners project outwards, speak to crowds, whereas I wanted something that would speak only to me. I wanted something to zip into a pencil case, something to carry in my hand luggage; I wanted a discrete surface to immerse myself in, to hold myself inside when the edges of my body seemed blurry. Textile artist Raquel Ormella expresses a similar sentiment when discussing her series of small embroideries All these small intensities, 2017–18: ‘Most of my work faces outwards, asking questions of the artist and the world; this work is focused inwards.’ [2]

Starting at one corner and building up the surface with tiny accumulative marks, I lost myself in this laborious vigil, the stitches following one another intuitively. The small textile became a map of segments, fragments of time compressed into colour and integrated into a continuous whole. I worked on trams, planes, in hospital rooms. The textile’s dense plane built up a record of time, labour, affect: a self-contained landscape of feeling. This is the devotion expressed through craft; the vigil of repetitive labour ‘like the returning sound of water’. [3]

DEVOTION AND TRANSITION

The term ‘pocket devotional’ traditionally refers to a miniature book of prayers, hymns, or other religious texts, which could be taken out and consulted in private moments, offering consolation and uplift. Among the well-to-do of medieval Europe, devotions were aided through the use of minutely carved objects such as diptychs or triptychs of ivory, with hinges that open to reveal minuscule Biblical scenes. [4] Even more astonishing are the Netherlandish boxwood prayer beads made between 1500-1530, possibly by a single artist or workshop, and which were ‘designed to be carried, perhaps suspended from a belt at the end of a rosary, and to be handled during prayer.’ [5] My small embroidery—able to be folded, carried on the body—came to fulfil a similar function. To open it up and sink my anxious, fractured attention into its soft surface, stitch by stitch, provided a sense of comfort and consistent devotion.

In helping to soothe the intense feelings of anxiety around my father’s illness, and my geographical separation from my parents during this time, Pocket devotional also became akin to a ‘transitional object’—the blankets or toys that, according to D.W. Winnicott, play a crucial role in the development of childrens' understandings of themselves as separate beings from their parents. [6] Often soft and tactile, these objects do not simply ‘represent' the body of the parent, but are psychologically indistinguishable from them. Begun in my father's hospital room, in some way the embroidery came to represent his fragile body immediately prior to his lung transplant, an incomplete and fragmented surface that needed to be made whole. The level of emotional enmeshment became clear when, a year or so after completing Pocket devotional, someone inquired about buying it—and I experienced an internal jolt of revulsion and panic, as though being asked to part with (and put a cash value on) an aspect of my father.

Importantly for my project, theologian Stewart Gabel has likened devotional religious objects (such as icons and images) to children’s transitional objects. Gabel theorises that, in the same way a blanket stands in for (or, psychologically, ‘is’) the parent, devotional objects operate as concrete materialisations of abstract notions of the divine. He argues that ‘the materialization of cognitive belief systems’ allows individuals ‘to sustain these belief systems, maintain an inner sense of satisfaction, and relieve anxiety.’ [7] In Pocket devotional, the (unconscious) entanglement of the textile with my father's body expands into a direct entanglement of the object with a sense of the divine.

THE MINIATURE

While this embroidery is very simple from a technical point of view, it does evoke some echo of the wonder that must, as historians Pete Ellis and Lisa Dandridge suggest, have struck the medieval recipient of a prayer bead upon opening its hinges. [8] Something of this is due simply to the miniature size, which draws the viewer inside its borders, pulling attention into the surface. In our productivity-driven society, there is also something vaguely astonishing about a small, somewhat insignificant object that nevertheless holds hundreds of hours of embedded time and labour. To sink so much precious time (which, after all, is money) into anything means it must be worth something—yet here it is, a rectangle, the size of a postcard, the labour massively overshadowing the result.

During a time of uncertainty and unsettled location, it’s no accident that I was drawn to a miniature scale. Aside from the practicalities of travel, the miniature is a means of containment. As Gaston Bachelard wrote in The Poetics of Space: ‘The cleverer I am at miniaturising the world, the better I possess it.’ [9] Shrunk down, condensed, the world becomes manageable. All its composite parts are visible. You can hold it in your hands.

[1] A. M. Larpent, Journals 1790–1830, HM 31201, CA: Huntington Library. Microfilm of the journals M1016/1-7, British Library. Quoted in Bridget Long, “‘Regular Progressive Work Occupies My Mind Best’: Needlework as a Source of Entertainment, Consolation and Reflection,” TEXTILE 14, no. 2 (May 3, 2016): 176–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2016.1139385.

[2] Anna Dunnill, “A Stitch in Time,” Art Guide Australia no 113, May/June 2018, 80. Reprinted in Art Guide Australia (online), accessed May 4, 2020, https://artguide.com.au/a-stitch-in-time.

[3] Long, “‘Regular Progressive Work Occupies My Mind Best’.”

[4] Sarah M. Guérin, “Ivory Carving in the Gothic Era, Thirteenth–Fifteenth Centuries,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/goiv/hd_goiv.htm (May 2010), accessed 30 September 2019.

[5] Pete Ellis and Lisa Dandridge, “Fabricating Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish Boxwood Miniatures,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bxwd/hd_bxwd.htm (April 2017), accessed 30 September 2019.

[6] Stewart Gabel, “D. W. Winnicott, Transitional Objects, and the Importance of Materialization for Religious Belief,” Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 21, no. 3 (July 3, 2019): 178–93, doi: 10.1080/19349637.2018.1467813.

[7] Gabel, “D. W. Winnicott”.

[8] Ellis and Dandridge, “Fabricating Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish Boxwood Miniatures.”

[9] Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 150.