A KIND OF COLLECTIVE BREATHING

2018–19

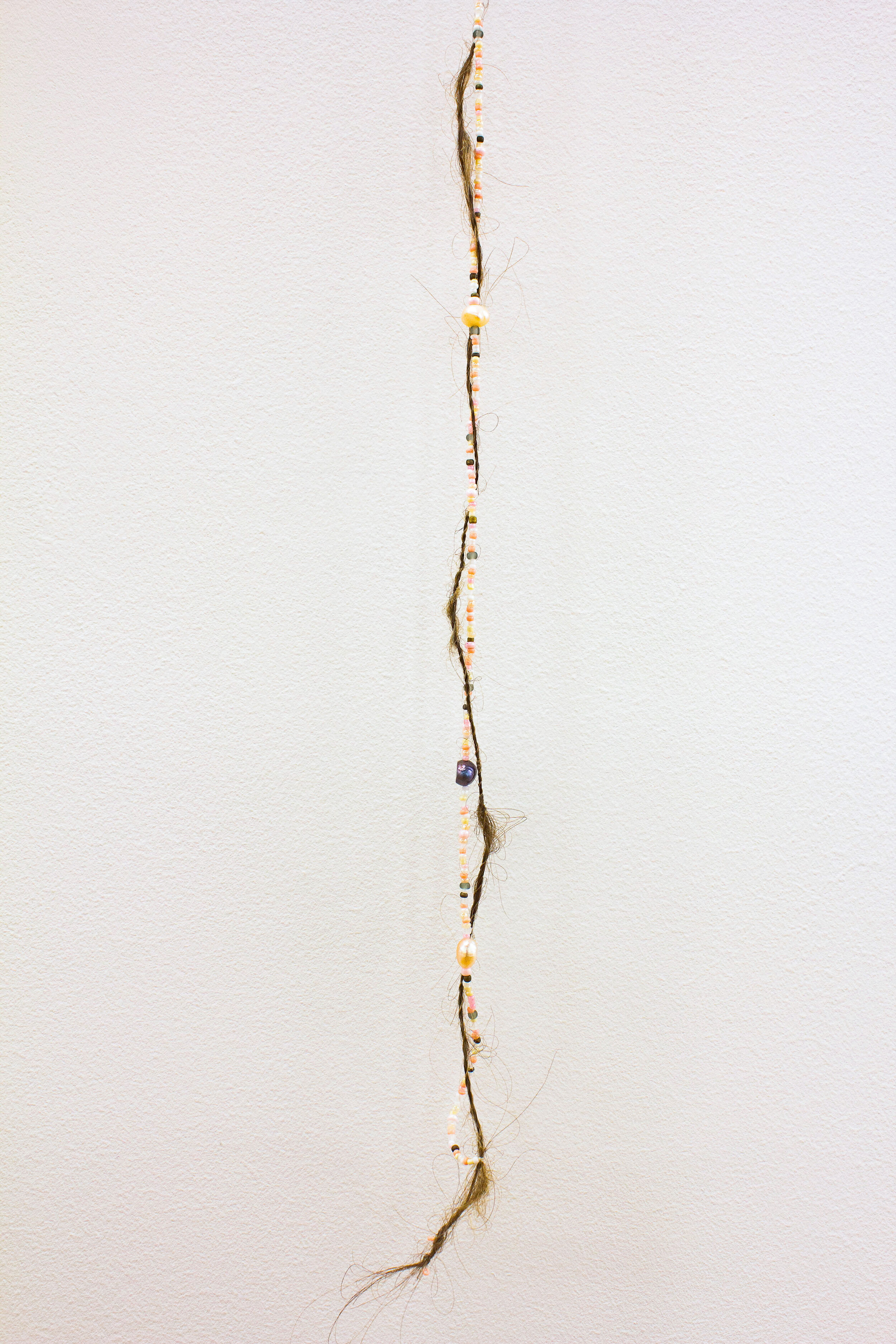

Anna Dunnill, A kind of collective breathing, 2018-19. Cotton, linen, metallic thread, wool, acrylic, human hair, handmade stoneware beads, seed beads, wooden beads, freshwater pearls, recycled glass beads, coloured pencil. Installation detail, The Stables, Victorian College of the Arts, 2019. Photo: WIlliam Normyle.

A kind of collective breathing was first exhibited in July 2018 at FELTspace, Adelaide. It was re-exhibited in a different configuration at The Stables, Victorian College of the Arts, in December 2019.

Installation detail: installed on two facing walls, The Stables, VCA. Photo: William Normyle.

Plaited, twisted and knotted, the threads in A kind of collective breathing are lines inscribed by a delicate but irregular hand. They are woven through with beads, a word that descends from Middle English bede - ‘prayer’ - recalling the function of a rosary, each symbolising a section of the ritual.

This work draws on the well-documented link between textile, thread, and language. In pre-colonial Central America, records were kept using quipu, systems of knotted yarn. In English, text and textile share the same Greek root; both stories and fabrics are woven.

Here, the language held within thread speaks to a reclaiming and re-orienting of prayer and ritual objects. It is a language formed through the slow accumulation of material; the embodied and time-based processes of hand-making.

Installation detail. Photo: William Normyle.

Installation detail featuring beads, freshwater pearls, and Renae’s hair. Photo: William Normyle.

Installation detail. Photo: William Normyle.

Installation detail. Photo: Anna Dunnill.

Installation detail. Photo: William Normyle.

KNOTS, BRAIDS AND BEADS

Excerpted from the written component of my thesis for Master of Fine Arts (Visual Art), 2019.

In this section, I consider the ways in which processes of knotting, braiding and beading can operate as an embodied language and a form of haptic prayer. I also explore the ways that knotted and intertwined threads can be a metaphorical means of connecting fractured parts of the world together, as well as holding and strengthening connections between the self and the community. Throughout this section, I look to the work of Chilean-born artist Cecilia Vicuña, whose thread-based practice reflects language, prayer and interconnection, as well as the material language of Janine Antoni’s 2001 work Moor.

A kind of collective breathing was first exhibited at FELTspace, Adelaide, in July 2018. The installation is composed of dozens of strings, each made up of numerous sub-parts that are plaited, twisted, knotted, beaded and adorned. The materials used include embroidery floss, metallic thread, wool, linen, human hair, glass beads, freshwater pearls, and handmade stoneware beads decorated with glazes or coloured pencil.

This work began with off-cuts of embroidery thread and yarn, leftovers from another project. I knotted their ends together into long strings and finger-crocheted all the way down the line, making the lengths stronger, more structural. As the work grew, I added beads, and thicker yarn, and human hair; I braided and twined threads into new sections. These latter parts happened mostly in the studio, but the structural work of the piece—the joining and crocheting of smaller threads—occurred everywhere: in lectures, on the tram, during quiet moments at my job as a gallery attendant.

Aside from a desire to use up scraps, this process of knotting and looping emerged because of a need to fill space, to occupy my hands. In my job I had to keep watch over a vast concrete-floored gallery. Hours plodded by with only a few visitors wandering through; the empty space ballooned out in front of me, filling with anxious thoughts, which followed me onto public transport and hovered while I watched TV. I was worrying a lot about my father, on the other side of the country. The medication he took for arthritis was silting up his lungs. When we spoke on the phone his breathing was laboured, raspy, and he broke into fits of coughing. I worried and knotted threads together, looped them with my fingers, working down the line, condensing and strengthening the fibres. It was a way of not only filling time but of measuring it, and of turning anxiety into something tangible.

Our lives are measured through breath. The first gasp and cry after the shock of birth, the last exhale before death, and everything in the middle, in and out. Our bodies synthesise chemicals into other chemicals, sophisticated machines regulated by a pump and a bellows, sometimes faulty, sometimes strong. In and out. Making this work regulated my own breath, helped slow it down, as I thought about my father’s breath, worked the thread with my fingers. Held his breath in my mind, in and out, as I twisted and knotted strands together, as I slipped beads over a needle, plink plink plink. This work became a ritual, became—no doubt about it—a prayer.

KNOTTING LANGUAGE INTO PRAYER

String represents one of the earliest examples of human object-making. The moment at which early humans discovered how to twine relatively short, weak fibres into longer, stronger strands is considered to be a turning point in human development—prehistoric textiles expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber calls it the ‘String Revolution.’ [1] [2] String, Barber suggests, kickstarted a whole new way of living. With innumerable applications in joining one thing to another, string unfurled the way for knotting, netting, handled tools, jewellery and garments. It is arguably at the core of our development into modern humans.

The foundational nature of textile to human identity is exemplified in the way that thread and language are conceptually linked across numerous cultures. In English, the Latin root word texere gives us text, textile and texture. We describe ideas as ‘threads’; we interweave narratives and spin yarns; we even type strings of code. Just as a piece of string connects objects together, and itself is made up of shorter twined fibres, language enables simple ideas to be combined into increasing levels of complexity.

String can also convey information non-metaphorically. The pre-colonial Inca kept records through knotted strings called quipus, now indecipherable. Outlawed by the Spanish in 1583, thousands of quipus were deliberately destroyed, the keys to their knotted code erased from cultural memory. However, it is thought that through combining different knots, colours and placement of strings, a quipu could hold sophisticated information, from accounting and census records to personal narratives [3], and possibly even a phonetic writing system. [4] Quipus therefore represent an example of a wholly tactile language, one made and understood through the hands.

Both spoken language and textile language originate with bodily expression, as British textile academic Victoria Mitchell points out: ‘Making and speaking, beginning with gesture and utterance, are both primarily tactile and sensory, of the body.’ [5] In my research, the language of thread conveys notions of haptic prayer through repeated gesture. While making the work, repetitively knotting, braiding and beading enabled my mind to enter a kind of ‘trance’ state akin to meditation or prayer. These actions also resulted in a gradual accrual of texture, a growing intensity of matter as more pieces are added together. In this work, the nature of the prayer was a specific but unarticulated hope around my father’s illness, the kind of magical thinking that often turns anxiety into ritual: If I do this, then this; if I keep looping these threads my father will be able to breathe again. In a recounting of the story of Sadako Sasaki and the 1000 paper cranes, Sadako is said to fold each successively smaller crane ‘as if it were a prayer’—another example of ritual brought about by illness. [6]

The tangible repetition of this work reflects the rhythms of breathing, in what might be read as an attempt to materialise breath: to call into existence long strings of air, chains of silvery bubbles, through the materials I worked with. (While making this work, I dreamed of my own breath as a length of pearls and sequins dripping from my mouth.) There is also an opposite reading. My father’s shortness of breath was caused by a disease called pulmonary fibrosis, which involves the scarring of lung tissue. ‘Fibrosis’ literally means thickening fibres, ‘the accumulation of excess fibrous connective tissue’ [7]—a parallel that struck me only after many hours spent looping, braiding and knotting thread into shorter, tougher lines. In unconsciously mimicking these physical symptoms, each string can thus be seen as an articulation of breath and of the scars preventing breath.

Both in terms of materiality and the repetitive actions of its process, A kind of collective breathing recalls the beads and knotted ropes used in many religious traditions as memory aids for reciting prayers and devotional texts. Catholicism has the rosary, Islam the tasbih, Eastern Orthodoxy the prayer rope [8]; Hinduism, Buddhism and B’ahai traditions have their own forms with different numbers and arrangements of beads. The word ‘bead’ itself comes from the Old English word bede, meaning ‘prayer’. [9] These objects free the devotee from consciously counting repetitions, instead moving the beads or knots rhythmically through the fingers until the recitation is complete, and allowing the mind to focus on prayer. The repeated gestures of braiding and knotting function in a similar way, allowing the hands to move automatically until the thread is complete. In this way, the repetition of gesture forms its own prayer language through the slow accumulation of material, the embodied and time-based processes of hand-making. The line held in these fibres is knotted with unspeakable, unreadable information, linked intimately to the hands and the body.

CONNECTING THREADS

My partner tells me that as an anxious small child, age four or five, she would perform a ritual to connect precious people and objects to her body, even in their absence. Touching a finger to the beloved object, and then to her body, she manifested an imaginary silver thread that ran between them. Threads holding more ordinary items—special bits of found ‘rubbish’, for example, scraps of plastic or shiny paper that she wasn’t allowed to take home—were connected to her leg or hand. But the people and objects most closely entwined with her sense of self—her mother, or her beloved teddy bear Kimmy—were touched to her chest. Connected to her by a silver thread.

A kind of collective breathing is composed of dozens of connected threads, which expand the work’s underlying prayer into a desire for collectivity and community. This stems from the physical distance between myself (in Melbourne) and my family (in Perth) during a time of familial illness, and the resulting feeling of fracture; as well as a broader sense of physical disconnection from others that underlies our technologically over-connected world.

In investigating the material expression of these ideas, I consider the work of Chilean-born artist and poet Cecilia Vicuña, whose practice constitutes a decades-long exploration into precariousness, interconnectivity, and paying attention. The quipu and its connective possibilities recur throughout Vicuña’s work, abstracted into single threads that link stones across a river, or expanded into huge lengths of un-spun wool hanging from ceiling to floor. In Vicuña’s 2016 collective performance work for documenta 14, Beach Ritual (Near Athens), participants were invited to use massive batts of blood-red wool to ‘weave a connection between their bodies and the sea’—working together to drag the wool into a huge 'living net’ along the shore. [10] These ideas are deeply entwined with Vicuña’s own culture and history. From the curatorial wall text of Cecilia Vicuña: Disappeared Quipu: ‘Textiles are integral to the daily activities and the spirituality of Andean cultures, conveying—through systems of weaving and the knot-making language of their quipus—an understanding of the sacred threads that interconnected all beings in the cosmos.’ [11]

In Vicuña’s practice, threads and knots are language, and assemblages become prayers. Begun in 1966, her ongoing series of sculptures, the Precarios, gather rubbish, scraps, twigs and feathers and assemble them into delicate clusters. These are held together with thread or seemingly just balanced; displayed on the floor or suspended in the air; or constructed in public space from nearby materials and left to naturally disintegrate. Here, discarded or overlooked objects become precious, almost revered, their materiality honoured as part of a greater interconnected body. Explaining the series’ title, the artist says: ‘Precarious is what is obtained by prayer. Uncertain, exposed to hazards, insecure. From the Latin precarius, from precis, prayer.’ [12]

The precarious and prayer-like threads of my installation are not only linked at each end but also often intertwined through twisting and braiding. String, as discussed above, is made up of short fibres twined together to make a longer one. Braids are made of three or more pieces of string or thread intricately interwoven: ‘a linear and planar form of woven knot that replaces the closure of the knot with the potential infinity of weave.’ [13] Symbolically, they represent interconnection of ideas or relationships. My installation also features sections of embroidery thread knotted into flat strips, using a sequence of patterns to make chevrons or stripes—materials and techniques that evoke the playground craft of ‘friendship bracelets’. Often made by children, learned peer-to-peer, and gifted between friends, these sections link two people through the repetitive, accumulative gesture of craft.

Another influence on A kind of collective breathing was Janine Antoni’s work Moor, 2001, a many-stranded rope twined by the artist over a period of several years. Eventually reaching 99.6 metres in length, the rope was constructed from items given to Antoni by friends and relatives. In video footage of the artist and her mother working together on this piece, Antoni explains that each element—clothing torn into strips, Christmas lights, hair, garlands, rosary beads, hammocks—‘connects intimately to a person’s life’, weaving the artist’s disparate personal community together into a strong sinuous ‘life-line’ or ‘umbilical cord’. [14]

Like Antoni, I had family assistance for A kind of collective breathing: my partner Danni helped me with the time-consuming task of crocheting the fine threads into slightly thicker strands. As we sat and worked together, the project opened up from being enmeshed in my own anxiety to being something gentle and shared, a point of connection between us. The piece also incorporates hair from a number of different people in my life—my partner, my housemate, close friends in Perth and Sydney, a uni lecturer who enthusiastically volunteered her hair-brushings. Different colours, different textures, curly and straight, thick and fine. I twined this hair into string and threaded it with seed beads, pulling together a group of people who are connected to each other only through my hands. Unlike Moor, however, the ‘ropes’ of my installation are delicate, fragile. They remain unattached to each other, suspended individually on the wall rather than twisted into a single strong life-line. This work expresses connection but also fragmentation; the threads spaced apart with room for a body to slip between.

In an artist statement that accompanied the 2018 exhibition Cecilia Vicuña: Disappeared Quipu at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Vicuña wrote: ‘Quipus are a metaphor for the union of all. / They were forbidden in 1583, yet they went on / undercover, still weaving our breath.’ Knotted, braided, beaded and twined, A kind of collective breathing materialises breath into an accumulated prayer for interconnectedness.

[1] Elizabeth Wayland Barber, Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years (New York, London: Norton, 1994), 42.

[2] Accurately dating this moment is admittedly hindered by the natural decomposition of fibre evidence. Barber puts the ‘String Revolution’ at 20,000-30,000 BCE (see above). However, perforated shell beads from North Africa that bear evidence of being strung together or sewn to a garment, a process presumably requiring some kind of thread, have been dated to 80,000 BCE—potentially pushing the String Revolution back by 50,000-60,000 years.

Source: A. Bouzouggar et al., “82,000-Year-Old Shell Beads from North Africa and Implications for the Origins of Modern Human Behavior,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, no. 24 (June 12, 2007): 9964–69, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703877104.

[3] Penny Dransart, "A Short History of Rosaries in the Andes,” in Beads and Bead Makers: Gender, Material Culture and Meaning, eds. Lidia D. Sciama and Joanne B. Eicher, 129–146, Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Women (Berg Publishers, 1999), https://doi.org/10.2752/9780857854025.

[4] Sabine Hyland, “Unraveling an Ancient Code Written In Strings,” SAPIENS, November 7, 2017, https://www.sapiens.org/language/khipu-andean-writing/.

[5] Victoria Mitchell, “Textiles, Text and Techne,” in The Textile Reader, ed. Jessica Hemmings (London, New York: Berg, 2012), 7.

[6] June Hill, “Sense and Sensibility,” in The Textile Reader, ed. Jessica Hemmings (London, New York: Berg, 2012), 39.

[7] Thomas A Wynn and Thirumalai R Ramalingam, “Mechanisms of Fibrosis: Therapeutic Translation for Fibrotic Disease,” Nature Medicine 18, no. 7 (July 6, 2012): 1028–40, doi: 10.1038/nm.2807.

[8] “Using a Prayer Rope in Prayer,” Orthodox Prayer, accessed October 30, 2019, https://www.orthodoxprayer.org/Prayer%20Rope.html.

[9] Merriam-Webster s.v., “Bead”, accessed October 30, 2019, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bead.

[10] Cecilia Vicuña, “Beach Ritual (near Athens),” Cecilia Vicuña, accessed November 2, 2019, http://www.ceciliavicuna.com/interior-installations/gz13cqaxja1axfpcflspp6nxu6kjhe.

[11] “Cecilia Vicuna: Quipu Desaparecido (Disappeared Quipu),” Brooklyn Museum, accessed September 27, 2019, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/exhibitions/3359/.

[12] Cecila Vicuña cited in Catherine de Zegher, “Ouvrage: Knot a Not, Notes as Knots,” in The Textile Reader, ed. Jessica Hemmings (London, New York: Berg, 2012), 137.

[13] Claire Pajaczkowska, “Making Known: The Textiles Toolbox—Psychoanalysis of Nine Types of Textile Thinking,” in The Handbook of Textile Culture, ed. Janis Jefferies, Diana Wood Conroy, and Hazel Clark (London, New York: Bloomsbury, 2016), 87.

[14] Janine Antoni in Loss and Desire, Art in the Twenty-First Century, Season 2 (Art21, 2003), https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s2/janine-antoni-in-loss-desire-segment/.